جدید

جدیدحرکت ساختارهای گرافنی بر اثر حرارت دهی – Heat gets graphene moving

حرکت ساختارهای گرافنی بر اثر حرارت دهی

محققان به تازگی دریافته اند که صفحات گرافن دو بعدی میتوانند به طور خود به خود، بلغزند، پیچ و تاب پیدا کنند، ورقه ورقه شوند و یا به شکل نوارهای باریکی از هم جدا شوند.

محققان به تازگی دریافته اند که صفحات گرافن دو بعدی میتوانند به طور خود به خود، بلغزند، پیچ و تاب پیدا کنند، ورقه ورقه شوند و یا به شکل نوارهای باریکی از هم جدا شوند.

James Annett و Graham L. W. Cross از دانشگاه Trinity اظهار داشتند که زمانی که به واسطه اعمال نیروی فشاری توسط یک فرو رونده الماسه، صفحات گرافن خم میشوند و در سطحشان چینخوردگیهایی ایجاد میشود، میتوانند به طور خود به خود و در دمای اتاق، به چندین نوار باریک (ساختارهای ربان مانند) تقسیم شوند.

تحقیقات پیشین نشان دادهاند که با اعمال حرارت، چین خوردگیهای موجود در صفحات گرافن، کاملا از بین رفته و سطح آن، صاف میشود. اما این دو محقق، در پژوهش حاضر نشان دادهاند که گرافن میتواند با استفاده از انرژی محدودی که از محیط اطراف خود کسب میکند، حرکت کند و تغییر شکل دهد.

تشکیل این نوارهای باریک نانومتری که پهنای آنها حدود nm 300 تا nm 2000 و طولشان حدود µm 5 است، در دمای اتاق به صورت خود به خود انجام میشود اما با اعمال حرارت یا تابش لیزر، میتوان این روند را تسریع کرد. طبق اظهارات این محققان، میتوان فرایند خودآرایی را به گونهای کنترل کرد که به اشکال پیچیده دست یافت. نکته قابل توجه دیگری که میتوان به آن اشاره کرد این است که با اعمال حرارت، چینش و شکلگیری مجدد گرافن، در تمامی نقاط صفحه گرافنی به طور همزمان انجام میشود.

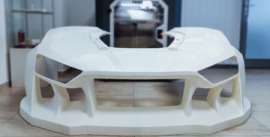

تصویر فوق ، تصویر میکروسکوپ نیروی اتمی (AFM) از نوارهای باریک گرافن سهبعدی ایجاد شده به واسطه خودآرایی ناشی از تماس سایشی را نشان می دهد.

Cross به این نکته اشاره کرد که “این رفتار تحرک خود بخودی که در شکلهای مولکولی یا پلیمری مشابه اتفاق میافتد، تاکنون در هیچ یک از ساختارهای بزرگ مانند سیستمهای گرافنی مشاهده نشدهاست”. او همچنین افزود ” این پدیده حتی با چشم غیر مسلح نیز قابل رویت است”

این پژوهشگران، همچنین پیشنهاد کردند که این روند فعال شدن توسط حرارت، از مکانیزمهای ترمودینامیکی ناشی میشود که طی آن ساختارهای مجزا و دو بعدی به منظور کاهش انرژی خود به ساختارهای سه بعدی تبدیل میشوند.

در صورتیکه طبق گفتههای Annett و Cross، این پدیده در مورد سایر مواد دو بعدی نیز اتفاق بیفتد، طی فرایند خود آرایی، تمامی ساختارهای دوبعدی میتوانند به ساختارهای سه بعدی پیچیده تبدیل شوند. از این مکانیزم، میتوان در ساخت نوسانگرهای فرکانس بالا و با کیفیت، سیستمهای تصویربرداری نانومقیاس، سوپاپهای میکرو سیال و نیز موتورهای حرارتی کوچک (مینیاتوری) استفاده کرد.

این روند، همچنین پتانسیل خوبی برای استفاده در حیطههای مختلف پزشکی نظیر تشخیصهای میکروسیالی و سیستمهای انتقال دارو، همچنین در زمینه مخابرات و حسگرهای موجود در قطعات اپتو-الکترومکانیک جدید را دارد.

Changhong Ke از دانشگاه دولتی Binghamton آمریکا، بر این باور است که این پژوهش، گام بزرگی در جهت تولید کنترلشده و در مقیاس انبوه نوارهای گرافنی خواهد بود.

Ke همچنین افزود: “تولید ورقههای گرافن با ابعاد، شکل و ساختارهای کنترلشده، از جمله موضوعات بسیار مهم و چالش برانگیز در اریگامی و کیریگامی (تا کردن و برش) ساختارهای گرافنی و کاربرد آنها به شمار میرود و تحقیقات Cross میتواند راه حل قابل قبولی برای این موضوع ارائه دهد”.

منبع : www.materialstoday.com

ترجمه : یاسمن نیک نفس

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Heat gets graphene moving

Single sheets of two-dimensional graphene can be prompted to slide, fold, peel, and tear into strips spontaneously, researchers have found.

James Annett and Graham L. W. Cross from Trinity College Dublin noticed that when a fold or pleat is created mechanically by pressing a sharp diamond tip into graphene, the sheet spontaneously tears into ribbon-like structures at room temperature .

Wrinkles form in graphene’s perfectly smooth structure when it is heated, previous research has shown. But now the two researchers have demonstrated that graphene can be guided to move and reconfigure itself driven simply by ambient energy.

“We have created a simple, folded-over and self-adhering con- figuration of graphene that turns out to animate the material, inducing it into self-locomotion to tear into ribbons,” explains Cross.

The formation of the tapering nanoribbons, which can be of any dimension from 300 nm to 2000 nm wide and up to 5 microns in length, occurs spontaneously at room temperature but can be accelerated with heat or a laser. The self-assembly process can be controlled to produce different and more complicated shapes in quite a reliable manner, according to the researchers. Moreover, the reconfiguration of the graphene can occur simultaneously at multiple locations across a sheet.

Atomic force microscopy image of three graphene ribbons formed from a fretted contact by self-assembly.

“This self-animated kind of behavior, known in roughly analogous forms for molecules and polymers, has never been observed for ‘large scale’ material such as our graphene systems,” says Cross. “The effect is almost visible to the naked eye!”

The researchers suggest that the heat-activated behavior is driven by a thermodynamic mechanism under which isolated, two-dimensional material tends to take up a lower energy, three-dimensional structure.

If the phenomenon is common to other two-dimensional materials, as Annett and Cross believe, it could provide a simple self-assembly route to transforming two-dimensional materials into more complex three-dimensional architectures. For graphene, the approach could enable the construction of high quality, high frequency oscillators, nanoscale imaging systems, microfluidic valves, and even miniature heat engines.

“We see applications in the biomedical space for microfluidic diagnostic and drug delivery systems, as well as in communications and sensing via new opto-electromechanical device concepts,” suggests Cross.

The researchers are now exploring the effect in other two-dimensional materials and hoping to build prototype devices.

Changhong Ke of Binghamton University, the State University of New York believes that the work represents a major advance in the manufacturing of graphene ribbons in a controllable and potentially scalable manner.

“The manufacturing of graphene flakes with well-controlled size, shape, and conformation has been a critical and challenging step in the pursuit of graphene origami and kirigami and their applications,” says Ke. “Cross’ work provides a plausible solution.”

دیدگاه کاربران